The Archives of Phi Gamma Delta

Archives Home Founders Traditions Today in History Historic Sites Leaders Exhibits/References Contact

______________________________________________________________________

Before and After Sweetwater

The Story of Bolivar G. Krepps (Jefferson 1849) and His Journey to California

By Richard H. Crowder (DePauw 1931)

Back to History Articles page

(For most of the following story we are indebted to George Hopper (Wittenberg 1932) who acquired photocopies of the letters of Bolivar G. Krepps and of his friend, Joseph Troth, from the Western History Department of the Denver Public Library.)

Pledge brothers sometimes scratch their heads over one test question: Identify Bolivar G. Krepps. A sharp neophyte would be able to answer: Krepps was the Jefferson "Delta" whom John T. McCarty met by chance on the banks of the Sweet Water in Wyoming on their separate ways to California in search of gold. The two had never met before, but they spent a warm fraternal evening together, talking of mutual friends at Jefferson College and of Phi Gamma Delta.

There is more to the Krepps story than that. A native of Brownsville, Pennsylvania, on the banks of the Monongahela, twenty miles southeast of Washington, Pennsylvania, Bolivar recalled a "brick house" and a "feather bed," which would indicate a degree of comfort (in contrast to a mud-and-log cabin and a straw mattress). He was born about 1827 at the peak of the power and influence of Simon Bolivar, the great South American liberator. One can easily conclude that the Krepps boy child was named for the Venezuela-born heroic leader of the fight for freedom in Columbia, Ecuador, and Bolivia (this last country named for the great man himself).

It is evident that young Krepps had a pleasant boyhood, a solid preparatory education, and hosts of friends not only in Brownsville but in nearby communities. (He writes with familiarity of young men from other towns along the Monongahela.) About 1846 he left home to matriculate at Washington. College, where he soon gained a reputation as "one of the most talented" students. By the autumn of 1848, however, he had transferred to Jefferson in Canonsburg. This may explain why McCarty had not known Krepps. McCarty had graduated from Jefferson in the June preceding and was reading law at home in Indiana.

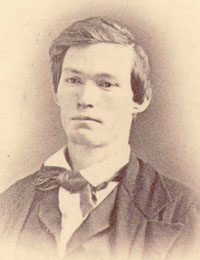

Picture of Bolivar Krepps, given by his sister to

Picture of Bolivar Krepps, given by his sister to

(and provided to us courtesy of) the

Western History Collection, Denver Public Library

Though we do not know the exact date of Krepps' transfer, we do know that he was a Jefferson senior in the autumn of 1848, for Naaman Fletcher (then president of Phi Gamma Delta) wrote to James Elliott on Saturday, November 11, that Krepps had been at Washington "a year ago." He also informed Jim that earlier in the week (on Wednesday) the Deltas had initiated Krepps, "a splendid fellow." In those days the procedures of initiation appear to have been less complicated than they are now. Bolivar G. Krepps, on November 8, 1848, was the twenty-second signer of the original Constitution, only the third to sign after McCarty had left Canonsburg shortly after Commencement on June 13.

Krepps was not in good health in early 1848. Maybe in the hope of improving, he joined a group of men bound for California to seek their fortune. He left Brownsville in mid-March, apparently taking riverboats to St. Louis, where he stayed four days longer than his companions. By early May, however, he rejoined the group in St. Joseph, Missouri. Two letters in this month mention his recent convalescence and his current robust health. Cholera had struck the camps of many of the adventurers. While Krepps was in St. Louis he observed how bad the epidemic was, and he discovered along the route of the Missouri that the disease was rampant. Only because the physicians aboard Krepps' boat were knowledgeable and skillful were they able to hold deaths down to four. Other boats had not been so lucky.

It is of interest to us that John T. McCarty left his home in Brookville, Indiana, on March 14, very near to the date of Krepps' departure from Brownsville. Because of different starting points and schedules, however, McCarty's group was about a month ahead of Krepps'. By the time Krepps arrived in St. Joe. McCarty had already crossed the Missouri into Kansas territory and was well on his way.

In St. Joe. Krepps and his friends bought two oxen to pull their wagon and one horse to ride. They had planned on three horses but could not find more than one. They had been advised not to buy mules, which could be hard to control. They were able to join forces with a local company among whom were some of the town's top citizens, the total number of men being just under a hundred. (One estimate was that some twenty thousand men would head for California "by the northern route," that is, through Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Utah.)

On Friday night, May 11, Bolivar and his friends slept in William Irwin's house, expecting to cross over into Kansas territory the next morning, but they were delayed till nightfall and had to spend the night on the river bank just opposite St. Joe. The actual trek, then, began on Sunday, May 13. They did not like to break the Sabbath in this way, but the circumstances had been forced upon them. During the first week they passed through territory belonging to the Sax, the Fox, and the Iowa Indians, beautiful and fertile land which the inhabitants cultivated so little as to cause Krepps to comment that they were "a lazy, filthy race," while acknowledging that the braves did carry themselves with noble dignity. He records that one evening a "fine specimen" came walking toward him and abruptly offered two pairs of moccasins in "trade," then sat down and waited. Krepps bought a pair but found them badly made.

The outdoor life was agreeing with Bolivar, for he was growing ''as fat and rosy as a country girl." He had a cot to sleep on and was getting plenty of rest. The food was coarse but palatable; he had developed a big appetite. The people he met were sociable and concerned (in contrast with the uncaring city dweller). He could appreciate now the pleasures to be enjoyed in the life of a nomadic gypsy. "It is surely romantic to encamp on a beautiful stream, then to fish and hunt. Besides it is pleasant to be out where you can act and think unconstrained by the gaze of a fashionable world."

By May 20 Krepps' party reached a camping spot on Blue Creek in Pawnee country. They had set up camp five miles back the night before, but had found the grass for the animals to be in poor supply; on Sunday morning they had moved on to this place, some 115 miles beyond St. Joe. During the next week they passed through some extraordinarily beautiful county. "I had no idea there was so much pretty land out of Pennsylvania."

He hoped to find letters from home when he reached California, but he was not homesick. Cholera was no longer a threat, and he himself was faring well with "the pure air and constant exercise." He admitted that, had he known what he knew now about the conditions of travel, he probably would never have ventured out of Pennsylvania. The food was incredibly good; the tent was waterproof. Bolivar was so adept at washing dishes that he half-facetiously suggested that he might become a professional cook when he returned to Pennsylvania. He assured his sister, Nancy, in fact, that if he didn't like California he would head for home at once.

Two and a half weeks later the company was encamped at Chimney Rock in west-central Nebraska, having traveled 520 miles from St. Joe. In addition to eating heartily. Bolivar was going to bed early and getting up early, "which nobody ever accused me of doing before." He and his friends had found the large company "both inconvenient and disagreeable;" so they were now in a group of only seventeen wagons and were having a splendid time. As they moved on westward along the Platte River, they were astounded by the beauty of the bluffs, which had been weathered into the shapes of "cities, castles, churches, and ruins of all kinds." One such bluff especially impressed Bolivar with a gushing rivulet racing "through a ravine almost inaccessible, the banks of which are adorned with cedar, while the edge of the rivulet is dense with sweet briars in full bloom and the space between the bank and stream is covered with different kinds of flowers, which have grown up promiscuously and in profusion, among which I saw two specimens of cactus in full bloom. They are beautiful."

On the morning of Tuesday, June 19, the party crossed the Laramie River, losing not a single article despite high waters. They were congratulating themselves both on their persistence ("we are at least one third of the way to California") and their foresight in laying in provisions. All along the North Platte they had seen supplies of abandoned "flour, bacon, wagons, and lame oxen." They were so well outfitted, however, that they "had no occasion to pick up or throw away anything." Luck with them, they would reach California by mid-September. Their health remained so good that the physician in their group had had nothing to do.

As the trek continued, Krepps and his friends passed through all kinds of climate "from freezing cold to burning heat," Sometimes the grass was insufficient, but nearly always there was good water. It was not unusual to have to detour from the planned route when word came back that the wagons would have a difficult time passing through.

The men crossed and re-crossed the Platte River, once on a raft made of three canoes nailed together. They had to pay three dollars per wagon. There was no serious accident though the waters were deep and rapid and many emigrants in other parties were drowned. Krepps himself saw a man drown "within thirty yards of a hundred persons who stood on the bank." The mishap occurred too swiftly for them to help the victim.

By July 4, the fifty men in the party had reached the Sweetwater River in Wyoming territory, but not before passing through country marred by serious impregnation of alkali, which had caused the death of many oxen. On the morning of the Fourth the men were ready to celebrate, as they did with a pint of French brandy and one of "Old Monongahela" whiskey. Fortunately there was plenty of ice. They observed "the day with as much enthusiasm as if they had been in a Still house and had Tom Jefferson himself for the orator." That afternoon Bolivar's immediate party of five wagons separated themselves from the others in order to find more grass for their cattle.

We know that three days later Krepps met up with John T. McCarty, who has recorded how thrilled he was at encountering a brother "Delta." Krepps himself did not mention the incident in his letters home. He had been welcomed into Phi Gamma Delta only a month or two before leaving college. The experience could not have meant as much to him as to that first man among equals of the Immortal Six, Brother Mac.[Editor's note-- Another reason Krepps did not mention the chance meeting: Krepp's sister did not know McCarty, and his family may have been opposed to secret societies, like some other families of our early members.]

Bolivar and the other adventurers skirted the Great Salt Lake Desert and then, after crossing the Continental Divide, came to the Humbolt River in western Nevada. The hardship that the oxen had to endure was incredible: "I have seen them trudge on with patient resignation for two days and two nights constant travel without a drop of water and scarcely a mouthful of grass." The road was lined with animals prostrated by the heat, the labor, and the general suffering. In one ten-mile stretch Bolivar counted more than fifty deserted wagons with accoutrements strewn all about.

As they approached their destination, the men thought they would need two more horses for their prospecting; so Krepps remained behind part of two days trying to buy the animals, but he had to give up and "walked to California." (He wondered if he would have to walk back home again!) Once in gold mining country, he was able to learn for the first time what news events had occurred east of St. Joe. He helped his friends to set up camp in the wilderness within reasonable distance of Sacramento, which they all visited at the end of September. The city struck Bolivar as one of "the funniest places you could imagine! The houses are nearly all tents and what are not are merely frames with muslin stretched over them and the streets are filled with trees." The party bought winter supplies at much lower prices than they would have paid in the mining camps: sugar, baking soda, syrup, pickled pork, flour, chili, and potatoes.

Having returned from Sacramento, the group broke camp on October 4 and set out for a new, more likely site to pan for gold. One of their number, Samuel Minehart, who had been in apparent health for the entire journey, died of apoplexy on that very first day. No physician being with them, the men tried every remedy and relief they could think of, but to no avail. They buried their comrade on October 5, and then moved six or eight miles into the wilderness.

They selected a "delightful" site some forty miles north of Sacramento at the edge of a stream. They all felt well and found the environment invigorating. Though they had been made aware that August and September often brought severe epidemics of fever and ague, they themselves were a robust crew. There were "plenty of Indians and any number of deer." Bolivar took great pleasure in hunting for sport.

In spite of the fact that the gold "diggings" were not yielding as much as they hoped for, the company agreed to stick together until the following May (about 6 months). There was always the chance of rich findings: "I frequently hear of men making three hundred dollars a day." Others were accruing much less; some were even in "dry diggings" and had no income at all. Bolivar told his family to advise any of his Brownsville acquaintances who inquired to stay home if they could find a paying job, but "if they can't, let them come." He had other advice: anyone coming over the Great Plains would be well advised to "pack on mules," at least beyond eastern Wyoming (Fort Laramie) and to travel as fast as possible through the alkaline country.

Some two weeks after their breaking of camp and moving on, Bolivar set out once again for Sacramento, undertaking the forty mile trip on foot through the forest, carrying a gun, a blanket, and enough food for the journey. He could buy a meal for a dollar, but there were no rooms available in the crowded city: he had "the privilege of selecting what tree I want to sleep under," He was extremely disappointed not to find letters from home awaiting him: "I feel more like crying than anything else." He instructed his family specifically in how to address a letter so that it would reach him without fail. He said he had seen two or three of his friends from neighboring towns in Pennsylvania and had received news of everybody back home, but that was not the same as reading letters from his own family, He promised, on his part, to write one or another "by every mail."

Krepps' last letter, addressed to his sister Nancy, was dated December 10, nine months after he had left home. He confessed irregularity in his own writing, partly from "laziness combined with a distaste for writing . . . the physical part, not the mental. That portion of the work is always a pleasure and more especially when my thoughts are of and for you," He was still bemoaning the total lack of letters from home. Letters addressed to him were doubtless in San Francisco, but he had no way of finding out.

The company had moved on, after his return from Sacramento, in search of better diggings, but they had been greeted by three weeks of discouraging rain. When at last the deluge ceased, he and four of his companions constructed a log cabin, where they were now expecting to pass the winter in comfort. They were on Matheney's Creek, a good fifty miles east of Sacramento at the foot of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The hunting was good; the grizzly bears were plentiful. [Matheney's Creek later became incorporated into El Dorado, according to Paolo Sioli's The History of El Dorado County, California, page 203. In the original article it was spelled "Matheny's".]

One day he spent the morning at the mines and made twenty dollars. "At noon two Indians reported two bears about a mile off; so I with several Missouri boys turned out for the sport and the meat." They killed one bear with about twenty shots, most of which went wild. He himself hit it twice, but he was modestly certain that neither one could possibly have killed it. The company had eaten the meat of two bears, had used the oil from the fat as shortening and as a substitute for butter, Again he reported a great improvement in his appetite as he pursued his adventures. In fact, the entire party was in "the very best of health" and had been able to buy ample food even though they had made only "between six and seven hundred dollars " among them.

Bolivar reported to his sister that he would probably be at home in Brownsville for the following winter. but would return to California. especially if this present experience proved that the climate agreed with him. California was providing "the finest views and most delightful days of any place in the world, Italy not excepted." (Of course, he had never been to Italy!) He speculated that California would become the most popular refuge in America for invalids, just as Italy was for Europeans. He contrasted the "mild and balmy" weather with conditions in Pennsylvania, where the air was freezing cold, and the Monongahela was "like as not grumbling under her burden of ice."

Here, on such a buoyant note, the letters of Bolivar G. Krepps stop abruptly. They are supplemented by two letters from one of Krepps' long-time friends, Joseph Troth, which tell of Bolivar's contracting typhoid fever (he spelled it "teaford") on December 9, 1849. There is some confusion here, for Bolivar was writing to his sister on December 10, in a letter full of high spirits and joyous exuberance. Troth's first letter is dated February 16, 1850. In the two-month interim after Bolivar was taken ill Joe could easily have been mistaken. At any rate, Krepps was ill about a month. Two doctors tried to help him, but he grew steadily worse, developing a debilitating diarrhea. He was aware that death was approaching and seemed resigned to his fate. At last, early on the morning of January 20, 1850, he ascended ad astra, "calm and composed and sensible till the last breath." Troth said he would settle his friend's accounts and take care of his belongings, bringing them back to Brownsville, probably in the autumn, anything Mrs. Krepps would like to have. Troth had written, in his semi-literate way, as comforting a letter as he could:

let us submit to the over ruling hand of providence with christin fortitude . . . we have lost a friend an associate who has be come endeared to us as a brother by the dificulty and trials that we have incountered with in the last year.

But ten months later Troth had not returned to the East. Still in northern California (Nevada City), he sat down, on December 17, 1850 to answer a letter Nancy Krepps had written on June 16.

His first letter (to Mrs. Krepps) had eventually reached its destination, probably in early May, for there was time for the Krepps family to send word of Bolivar's death to his friends and brothers at Jefferson College. The fraternity minutes record that on May 27 Thomas W.B. Crews was appointed chairman of a committee to draft resolutions of Phi Gamma Delta with regard to the death of their Brother. No doubt a copy of these resolutions was sent to Bolivar's relatives in Brownsville.

In his letter of December 17, Troth recounted for Nancy more particular circumstances of her brother's death (nearly a year earlier). The doctor had suggested that his companions say as little as possible about Brownsville, for resulting depression might interfere with the effectiveness of the medicine. (Troth himself was somewhat skeptical about this direction.) Bolivar, however, had mentioned Brownsville several times as he woke from sleep. Once, as he roused, he had asked how far the boat was from Brownsville. When told that he was in California, he had admitted that his mind had been wandering.

In the week and a half before his death he had become weaker and weaker, could hardly ask for a drink of water. Joe Troth had remained beside him on the Thursday night, a week before he died. At one point, he called Joe and asked him to wind up his affairs and inform his friends. Even this brief request had completely exhausted him. He had never regained enough strength to ask for anything more. Troth told Nancy that when he had left Matheney's Creek for Nevada City, Bolivar's grave was enclosed "with a pole fence," but he expected to return soon and would see to it that the plot was surrounded "with palings and properly secured."

As far as we know, Krepps was the first of the Delta brotherhood to die. In his last illness, he was at least supported by faithful friends, in contrast with Dan Crofts, who died two years later in miserable solitude in Louisiana. We can be thankful, however, that both men left behind them a fraternity strong enough to be vigorous and vital today.

A tinge of irony colors the ending of this story. Fletcher and Crews were still at Jefferson College; Gregg was studying law in Washington, Pa., and Crofts, before he left for Louisiana, was also studying law in Ohio; and Elliott was first teaching school, then pursuing newspaper work, and at last entered into the practice of law. Alone of all these early brothers, McCarty was in the West. At the time of Bolivar's death, Mac was tiring of the search for gold and was resolving to become a lawyer in earnest. As an ambitious young man, he settled in Marysville, not more than twenty-five miles away from the brother Delta whose hand he had clasped on the banks of the Sweet Water six months before. Had McCarty known of Krepps' serious illness, he most assuredly would have come to Matheney's Creek to administer comfort to a man, who, though Mac had seen him only once, was bound to him as with hooks of steel in the Fraternity of Phi Gamma Delta.

For more information:

Sweetwater River map: www.pbs.org

Back to History Articles page