The Archives of Phi Gamma Delta

Archives Home Founders Traditions Today in History Historic Sites Leaders Exhibits/References Contact

______________________________________________________________________

Reprinted from The Phi Gamma Delta Volume 101, Numbers 3 and 4, and Volume 102, Number 1

(Spring, Summer, and Fall 1979)

The Thirteenth Fiji

Thomas W.B. Crews (Jefferson 1850)

Called "that god of boys" by the Founders

By Richard H. Crowder (DePauw 1931)

Back to History Articles page

Information for this series of articles was drawn from Tomas Alpha, Crew's diaries, and In Retrospect by Sue Reed. We are grateful for the help of Elzie H. Musgrave (Missouri 1933), Crews' grandson.

Information for this series of articles was drawn from Tomas Alpha, Crew's diaries, and In Retrospect by Sue Reed. We are grateful for the help of Elzie H. Musgrave (Missouri 1933), Crews' grandson.

Links in this article lead to related pages and articles on the Archives web site.

Thomas W. B. Crews was just 16 when he signed the constitution of Alpha Chapter at Jefferson College, Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. Born in a country house in Henry County, Virginia (near the North Carolina border), on March 16, 1832, he was the great-grandson of a Revolutionary soldier who had fought in the decisive battle of Yorktown a half-century before. In college years, Tom remembered great country dinners and "good old times at Leatherwood," apparently the name of his family's plantation.

For 14 years Tom was reared as a Southern agrarian gentleman, ingrained with the ideals of chivalry, honor, and bravery. His mind was cultivated by studies preparing him for college, not only arithmetic, English grammar, geography, the elements of history, and the "elementary authors" in Latin, but also Caesar, Sallust, and Virgil, and even certain Greek texts such as the New Testament. He learned to ride a horse, to use a rifle, to be courteous to all, and to be a leader.

In 1846 the Crews family followed the trend of many Virginia gentleman farmers in moving to Missouri. Some had migrated more than 25 years previously (before the territory was a state), settling along the Missouri River westward from the Mississippi. Land being frequently offered for as little as $1.25 an acre at "sheriff's sales," soon these transplanted Virginians had become large landholders in their new locale.

Because cultural developments were a century behind what they had left in the East, they banded together in nostalgic self-preservation and formed a "Little Dixie," where they pursued Southern cultural and political activities. Besides managing their farms, many of the men became physicians, lawyers, and public servants. When the Crews family arrived, they chose to settle at Glasgow, farther up the river in the center of the state.

The following year Tom went back east to Canonsburg and matriculated as a freshman at Jefferson College. Like other first-year students, he followed the common curriculum (no "electives"), concentrating on mathematics and Greek and Latin classics. In the 4 years, Jefferson students were all introduced to such subjects as surveying, navigation, and chemistry. In the last term of their senior year, they were confronted with moral philosophy, political economy, geology, agricultural chemistry, physiology, and evidences of Christianity and were still reading Latin. Hardly a schedule for a lazy man!

During his first 3 or 4 months, Tom met several members of the Franklin Literary Society and was himself elected to membership on December 17, 1847, assuming his seat as a regular member two weeks later. Names familiar to all of us were already on the Society's roll - McCarty, Fletcher, Wilson, Elliott, and Gregg. Croft (the other member of the Immortal Six) had been a member but had requested and been granted "an honorable dismission." The name of Crews occurs frequently from now on in the minutes of the Society. For example, on February 18, 1848 (he was not yet 16), he was permitted to read his contribution to the discussion: "Is the present war with Mexico just a war on the part of the U.S." and was excused on this occasion from the custom of speaking twice in the debate.

The Franklin men who founded Phi Gamma Delta later in the spring grew very fond of "little Crews," as McCarty called him. Less than 2 weeks after they had adopted and signed their constitution, they invited Tom to join them. He signed the document on May 12, 1848, the thirteenth member, "T. W. B. Crews" in bold hand. He participated enthusiastically, meeting with the others by moonlight at Tillie Hutchinson's spring house, in John McCarty's room at "Fort Armstrong", and by flickering candlelight in the woodhouse of the Seceder Church a mile from town.

After commencement in June, Crews joined McCarty on an Ohio River boat from which Mac debarked at Cincinnati, Tom continuing to his home in Missouri on what he described as a safe but long and tiresome journey. Mac and Tom were never to meet again, though they maintained correspondence. (All the members of the Delta Association were great letter writers.) Tom had not been home long when he received a letter from Gregg dunning him "for the 3 bits he [borrowed] at the Eagle Saloon!!!" "Little Crews" was not above a drink now and then.

Back at Jefferson after the summer holiday, he sent letters at least thrice to Elliott asking for help in certain writing tasks. Once he requested a piece of prose or poetry suitable for the autograph album of a girl visiting in town. At another time, when he was assigned a composition to write, he wanted suggestions from Jim. His subject was to be rather fanciful - "Colloquy of the Stars" - and he needed a touch of humor. In November 1848 he was chosen to represent the Franklin Society as one of two "Select Orators" in an all-college "exhibition" to be held 4 months later.

About 6 weeks before the affair, he wrote to Elliott asking him to compose a 12-minute speech for him on the subject of "The Star-Spangled Banner." He wanted it to be ''as eloquent as possible." He supposed it would take Jim no more than "a few hours" to write, and he would like to have the finished product by February 20 or 25 at the latest. (This would give Jim less than 2 weeks to prepare the document.) Tom signed his letter "Your devoted friend!" Who wouldn't be devoted to someone who would do so much for him? It is obvious that Crews had no compunction about such a problem as plagiarism. It was in fact surprisingly common for student orators to read speeches prepared by others. When the 2-day festival opened on March 29, Providence Hall at Jefferson College was elaborately decorated, a band played, a preacher prayed. Crews was second on the program, "his" oration received loud plaudits from a large audience. The labor had been Elliott's, the glory was Tom's. One can imagine his beguiling delivery with his Southern accent.

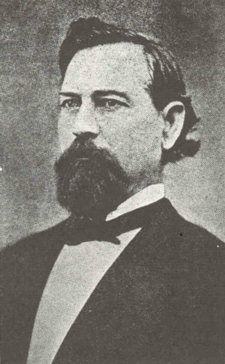

Picture: T.W.B. Crews as a student, c. 1850. Note the Phi Gamma Delta Badge on his waistcoat. Copy courtesy Washington and Jefferson College Library.

Picture: T.W.B. Crews as a student, c. 1850. Note the Phi Gamma Delta Badge on his waistcoat. Copy courtesy Washington and Jefferson College Library.

By coincidence, on the second day of the exhibition, March 30, McCarty, on his way to California, was on board the Sacramento sailing up the Missouri. His journal entry: "Early in the evening we passed Glasgow, a small village, the residence of a particular friend of mine, T. W. B. Crews, a Brother Phi Gamma Delta, who is now at Jefferson College, Pa." One wonders what his reaction would have been had he known that, on the day before, Tom had delivered an oration written by his Brother Phi Gamma Delta Jim Elliott. He might have been amused, for he himself was known to commit an occasional peccadillo. In writing to Elliott a description of the program and Crews' participation in it, Crofts called Tom "that noble and magnanimous boy." He must have been charismatic indeed to entice Jim Elliott to spend "a few hours" writing his speech for him.

Crews may have been a charming lad, but he was subject to as many fines as any other member of the Franklin Society. The fines were small (generally 10 cents), but they were numerous. Once he upset an ink bottle "on the Recording Secretary's minutes" (accident or mischief?). He was fined for missing roll call, for being out of the room for more than a half hour, for making a disturbance in the library, for keeping borrowed books too long, and for referring to his notes during debate.

On the other hand, he accepted responsibility in the conduct of the Society. As a freshman and again as sophomore, he served on the Society's committee on arrangements for the upcoming commencements. Twice he was put in charge of the Society's nearly 2500 books during vacation times, his home in Missouri being too far away for him to make the journey by boat. Once he debated the negative side of the question: "Are short terms of political office desirable?" He lost the decision. (Would he have been more successful if Jim Elliot had written his speech?)

After his initiation into Phi Gamma Delta on May 12, 1848, Tom Crews was far from apathetic about his membership. We have it on the authority of his son, also named Thomas B. Crews, that as an undergraduate McCarty's "particular friend" had the Greek letters tattooed on his left arm. By his junior year he was assuming more and more responsibility. In September 1849, he was chairman of a committee instructed to arrange for signs for the Delta Association. At another time, he helped in the selection of passwords. When late in 1849 the "Original Six" (they were all Graduate Brothers by this time) were planning some reforms in the initiation of new men as well as other matters, they took 2 younger members into their confidence - David Hall [Jefferson 1850, pictured left], the 19th initiate (the last that the Immortal Six had brought into the order before the 1848 commencement) and Tom Crews. In December 1849, Crews joined Gregg and Wilson in discussing plans for a meeting of the founders to talk over alterations, corrections, and additions to the original constitution and arranging to have it printed neatly and elegantly along with a book of rituals to be distributed to presidents of new chapters as they were installed. Though most of the ideas came from Gregg and Wilson, Crews was on hand to give suggestions and undergraduate assent. On the first of January, Gregg delegated to Crews the responsibility for the printing of the documents (the raising of funds being one problem). It was too bad, they thought, that the materials would not be ready in time for the installation of the new Chapter at the university at Nashville, Tennessee. (This installation took place on January 9, 1850, but the chapter failed to last through the year.) Though Wilson wanted Crews to act with deliberate prudence, Gregg urged him to get the job done in all haste. We are certain that Tom's energy would not allow him to draw out the process.

After his initiation into Phi Gamma Delta on May 12, 1848, Tom Crews was far from apathetic about his membership. We have it on the authority of his son, also named Thomas B. Crews, that as an undergraduate McCarty's "particular friend" had the Greek letters tattooed on his left arm. By his junior year he was assuming more and more responsibility. In September 1849, he was chairman of a committee instructed to arrange for signs for the Delta Association. At another time, he helped in the selection of passwords. When late in 1849 the "Original Six" (they were all Graduate Brothers by this time) were planning some reforms in the initiation of new men as well as other matters, they took 2 younger members into their confidence - David Hall [Jefferson 1850, pictured left], the 19th initiate (the last that the Immortal Six had brought into the order before the 1848 commencement) and Tom Crews. In December 1849, Crews joined Gregg and Wilson in discussing plans for a meeting of the founders to talk over alterations, corrections, and additions to the original constitution and arranging to have it printed neatly and elegantly along with a book of rituals to be distributed to presidents of new chapters as they were installed. Though most of the ideas came from Gregg and Wilson, Crews was on hand to give suggestions and undergraduate assent. On the first of January, Gregg delegated to Crews the responsibility for the printing of the documents (the raising of funds being one problem). It was too bad, they thought, that the materials would not be ready in time for the installation of the new Chapter at the university at Nashville, Tennessee. (This installation took place on January 9, 1850, but the chapter failed to last through the year.) Though Wilson wanted Crews to act with deliberate prudence, Gregg urged him to get the job done in all haste. We are certain that Tom's energy would not allow him to draw out the process.

Gregg was in Washington, Pennsylvania, the seat of the Beta Chapter, less than 10 miles south of Canonsburg. He and Crews corresponded frequently and continued to visit each other. In February Gregg wrote Tom acknowledging the 15 dollars Tom had sent in his last letter (obviously the repayment of a loan). He was looking forward to Crew's visit to the county court house in Washington, for some interesting cases were coming up. Even now, Tom was evincing interest in law.

As the spring term came to a close, Tom took on other responsibilities. He was appointed to the committee (probably in company with some Graduate Brothers) to revise the constitution and to draft bylaws for the Fraternity. On May 27, 1850, he became "chairman of a committee to draft resolutions in reference to the decease of our late Brother, B. G. Krepps." This was the Phi Gamma Delta that McCarty had met by chance on the banks of the Sweet Water in Wyoming. He had died the following December of typhoid fever. Word had reached his Brothers at Alpha Chapter only some months later.

Also in May Tom sponsored the initiation of William E. McLaren, who had been initiated into the Franklin Society the preceding July. The two men became lifelong friends. On the third anniversary of his induction into Phi Gamma Delta (that is, 1853), McLaren was to write to Crews from his home in Cleveland and report that he had just drunk a glass of sherry to Tom with the following toast:

Here's to your health in this glass of wine,

Your health in this glass of wine, Tom Crews;

Watch over the flames of your friendship, Tom,

As I do watch over mine,

Thine McL.

To this Crews would reply:

And here's a bumper to you, friend Mac,

Of the richest Muscatelle.

That vestal fire is still burning, Mac,

Brighter than flames of hell.

And here's a pledge to you, my friend,

In the juice of the red grape given.

I'll watch that flame till life shall end,

And light it then in heaven.

And watch the flame they both did. By the time of this exchange of toasts (1853) Crews was about to begin his law practice in Marshall, Missouri. McLaren entered the Episcopal ministry, eventually becoming the Bishop of the Diocese of Chicago. He would serve as the Fraternity's Archon President from 1901 to 1903.

Tom Crews was elected president of Alpha Chapter for the 1850-51 school year, but did not return to accept the honor or execute the responsibilities. Instead, he transferred to Union College at Schenectady. A fair speculation is that he expected to act in the role of legate in establishing a chapter of Phi Gamma Delta, but the climate was unfavorable, for there were already six fraternities at the college - all founded there, in fact: Kappa Alpha Society (1825), Sigma Phi and Delta Phi (both 1827), Psi Upsilon (1833), Chi Psi (1841), and Theta Delta Chi (1847). For a college so small that would seem to be a sufficiency. (Phi Gamma Delta entered Union College in December 1893.)

Our Fraternity is fortunate to have in its Archives the diary that Tom Crews kept carefully for four months from the first of the year 1851, recording his daily activities both at Union, in the town of Schenectady, and elsewhere. He had apparently stayed at the college during Christmas vacation, for the trip home would have been much longer even than from Canonsburg. On New Year's Day he and a friend followed the custom of young men in those days of paying calls on the ladies. (They did not find the President's wife at home.)

When the winter term opened, in addition to attending recitations, he was working in the office of a local judge in preparation for a career at law. But he was leading a jolly social life as well: shooting the breeze with friends, flirting with the town girls (one day he and his chum chased a couple of young things up and down the streets, just for the fun of it, and on another occasion he amused some passers-by when he winked broadly and boldly at some girls in the street), and enjoying periodic "bolts" at Captain Jackson's bar to ward off the effects of the "Siberian" weather.

He was a conscientious student, as a general rule rolling out of bed at five-thirty or six in the morning and many times not retiring until midnight. His pal Jim Crocker and he would often spend the night in the room of one or the other, studying, yes, but also gossiping, writing letters, eating snacks. He enjoyed books (for example, Louis Adolphe Thiers' French Revolution and James Fenimore Cooper's Red Rover). There were frequent chapels, church services, convocations, visiting lecturers. And there was campus politics. At the meeting of the senior class on January 13, Tom, the lone Delta, sided with the Chi Psis, the Kappa Alphas, the Theta Delta Chis, and the Delta Phis in determining a day to elect a class marshal.

On February 11 Tom was not feeling at all well, and the next day he came down with a case of the mumps which kept him from classes till the third of March. Crocker and his other friends brought him his mail and often stayed to visit. After two weeks he could stand his rough beard no longer and had a barber come in to shave him, but he acted very unwisely afterwards in rubbing camphor on his tender skin so that his face was covered with blisters! In a couple of days, however, he was feeling well enough to venture outside and even to go to Judge Wright's office, but at best the mumps had been an unpleasant ordeal.

On the Saturday of his birthday weekend he received a check for $200 which he cashed at once in order to pay his bills. With what was left he bought a new suit. This splurge did not cheer him up, though, for on Sunday, his nineteenth birthday, he had a melancholy time of it, going to church twice, attending prayers once, and writing a letter home. In spite of this activity he was lonely all day, "thinking of the past, the future and the present. 'Tis sweet to think." Bittersweet, one would have to say.

On the following Tuesday he had what he thought was a bad toothache, which developed on Wednesday into a fever, a headache and a sore throat. We can speculate that it was the twenty-hour flu, for in a day or two he felt well enough again to go for a horseback ride in the country with Crocker. He was fully recovered by examination time, when he turned in a good performance.

Four weeks of vacation followed. He went sightseeing in nearby Albany and, in spite of inclement weather, met his Uncle James Crews in New York City, where he attended the theatre and did some shopping. On the night before his uncle was scheduled to leave for Virginia, Tom had planned to go up to Boston to look around, but the weather was still too bad for him to undertake the trip. So, next morning, after he had seen his uncle off, he took the seven-o'clock boat to Albany, where he arrived at three-thirty in the afternoon. His train for Schenectady left Albany at six-fifteen. It hardly takes twelve hours today to go from New York to Schenectady!

The last two weeks of his spring vacation he spent reading law, going to a concert, walking about the town and countryside. When the new term opened, he took up lodgings with S. Ramsey, a Phi Gamma Delta from the Beta Chapter at Washington College. The sense of intercollegiate brotherhood was beginning to develop. There were now four chapters, Epsilon having been installed at North Carolina six weeks before. On the evening of the second day of the session Tom went to call on a new girl in town, who beat him so badly at backgammon that he left, apparently in a chauvinistic huff. You can't win 'em all!

The diary stops with the entry for May 4, which was a Sunday, ten days into the spring term. Tom, as usual, went to church and sat with Mrs. Wright, who offered him a place in her pew at any time in the future. We know that after his commencement he stayed on in Schenectady reading law in the judge's rooms and learning the procedures of running an attorney's office. A year later, however, he was back home. On July 6, 1852, Elliott wrote to Sam Wilson, "Crews is in Missouri, reading law." He was studying in an office in Marshall, county seat of Saline County, across the Missouri River from Glasgow. In two or three years he had passed his examinations and was established in practice at Marshall.

On March 16, 1857, he celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday. That spring he met a lovely twenty-year-old girl who was attending finishing school at nearby Boonville, some fifty miles southeast of Marshall nearer St. Louis on the Missouri.

Virginia Jeffries (nicknamed "Jinnie"), like Tom, was of transplanted Virginia stock, her family having made the long journey some years before Tom's and settled in Franklin County just beyond St. Louis County. Her father acquired property where Gray Summit was later to be located, and established a homestead two miles west of Union, where Virginia was born. (All these little towns were so close together that they actually amounted to a single community.) At Boonville Jinnie studied conversational French, piano, art, and literature (that is "proper" novels and poems) - quite a different education from Tom's. She became an accomplished, charming lady. When Crews married her, she proved to be a gracious wife and hostess. The young couple settled in Marshall. where Tom's law practice flourished. Eventually they became the parents of five sons and two daughters.

All was not tranquility, however, for during the next five years political unrest was brewing. Except for pockets of "Little Dixies," most of the people along the Missouri were Union sympathizers. Tom and Jinnie in Marshall were not in a situation of political compatibility, in spite of Tom's satisfactory practice and their social popularity. Jinnie's family and well-to-do friends in Franklin County were in the same position. As anger rose, violence occurred on both sides, Union and Southern sympathizers being guilty alike. When at last war came, the entire region was subjected to "extreme lawlessness."

Tom joined the Missouri State Guard on May 28, 1861, some six weeks after the surrender of Fort Sumter that marked the beginning of the war. As college man, successful lawyer, well-bred gentleman, and experienced horseman, he was appointed Captain of the "Saline Mounted Rifles" in a division of the Second Regiment Cavalry-Sixth Military Division, Missouri State Guard. [See Crews' uniform epaulets in the Museum]

When in the following August the Seventh Kansas Cavalry crossed the line into Missouri, Crews and his fellow Rebels drove them back home. For exceptional bravery in this battle Tom was promoted to lieutenant-colonel. As a dashing fearless officer on horseback he subsequently saw action in several battles in the state, including Carthage and Boonville (where he had met Jinnie four and a half years before).

In the autumn of 1861 the Rebels were pushing the Union forces into surrender at Lexington (halfway between Marshall and Kansas City). The night before the Union capitulation, Tom became so ill with a fever that he had to be hospitalized. After a few days his father came from Glasgow and carried him home to Marshall in a horse-drawn buggy. Tom was to see no more action in battle, for he spent the next two months in bed attended by a physician and his "tender, affectionate" wife. The summer's campaigns had been too arduous; all winter long he was afflicted with acute rheumatism.

On November 24 his mother died while visiting her ailing son. Tom was granted permission from the Union authorities to attend her funeral in Glasgow, though on the very night of her death he had to hide for fear of being taken prisoner. On the way to and from Glasgow he met with constant harassment from Federal soldiers, but he made it safely back home, where he passed the winter as a virtual invalid.

On Tuesday, March 4, 1862, Tom was sitting in his house with Jinnie and a relative of hers, Samuel W. Holland. At one point Tom went to the window and saw a body of Union Cavalry surrounding the town, obviously preparing to take the two men captive. By a ruse Holland escaped. Jinnie begged Tom to follow suit, but he stood his ground, telling Jinnie it would be "impolite"(!) to run away. When the Union soldiers at last knocked on the door, they inquired for Holland. Crews could honestly say he did not know where his kinsman was. Forty-five minutes later the Federal men returned and arrested Tom, who gave up the only weapon he had - a Colt revolver.

Taken to the county court house (familiar territory to him as a lawyer). he was brought before a Captain Kiser (an acquaintance of his) and was paroled to the next morning, two friends acting as surety for him. He spent Tuesday night in his own home.

On Wednesday morning he reported at eight o'clock and was taken to the Union prison at Arrow Rock, a hamlet very near Marshall. Again he was released on his own recognizance till the next day and spent the night, by cordial invitation, in the house of a generous friend. Crews was never after that required to provide security. During Wednesday the Union sympathizers at Marshall (with no exception) all signed a petition for Tom's unconditional release and forwarded the document to the commanding officer at Boonville (and probably on to St. Louis). On Thursday, after the prisoners at Arrow Rock were marched to Boonville (less than twenty miles away), Crews was granted permanent parole, his duty being to report to the colonel at Boonville weekly "by letter or in person." He never saw the other prisoners again.

On Friday, March 7, the colonel granted Tom permission to do as he had outlined. On Saturday he took the stagecoach to Tipton (twenty-five miles south), whence he caught a train for St. Louis on Sunday. Next day, having consulted with acquaintances about protocol and procedure, he interviewed various Union officers and was treated with courtesy and kindness. He was paroled to report to the colonel's office in St. Louis each month (again by mail or in person). He is said to have been the first Confederate prisoner to have been paroled in the state of Missouri.

Tom remained in the city until Wednesday, no doubt calling on his acquaintances and making new contacts. On his return to Marshall he stopped off a day or two in Franklin County, where he found that Jinnie's father was about to go to St. Louis to do what he could for Tom's release, for he had not heard about his son-in-law's parole. Mr. Jeffries was influential in public affairs and was known in his community as not favoring secession, in spite of his Virginia background. After a short stay at the Jeffries farm, Tom went on home by way of Boonville, where his horse and his Colt pistol were returned to him. He had been separated from Jinnie and the children a little more than a week.

In his war-time diary Tom made particular note of his own attitude toward Union soldiers: he never permitted cruelty or thievery by his own troops and would not allow them to disturb Federal soldiers doing civilian duties. As a result the Union men bore no resentment toward him, indeed did all they could to protect him, as evidenced by his treatment in Boonville and St. Louis. Ironically, nearly all his own cavalry troops were eventually captured, many of them held in Alton Prison, just above St. Louis on the Illinois side of the Mississippi.

Sometime after his parole, Tom decided to move Jinnie and the children to the Jeffries property in Franklin County, where they would stand a better chance of avoiding Union harassment. They established a new household, with the help of slaves, in an old frame house - substantial but not particularly aesthetically pleasing. Here, four of their seven children were born.

Meanwhile, Tom in reporting monthly to Union Headquarters in St. Louis, very prudently (and, one must say, cleverly) established solid business contacts so that, when the war was over, he resumed his law practice not only in Franklin County, but in St. Louis itself.

In a new constitution, Missouri, of course, abolished slavery, but Tom and Jinnie's slaves stayed on as devoted servants. Presumably, Tom had been a kind master. The constitution, however, denied the vote to Southern sympathizers, and for the next half dozen years the Republicans held power. By 1873, though, the "Southern element" (that is, the Democrats) had recaptured control of the state government and organized a state constitutional convention for 1875. Crews represented Franklin County around the "Union-Gray Summit" area and helped to institute yet another constitution, this time in reaction to Republican excesses and the national economic panic of 1873.

Tom had become a prosperous farmer and a well-established lawyer. In 1879 he and Jinnie decided to build a manor house of brick and turn the old frame house into a kitchen with servants' quarters upstairs.

They chose a site high on a hill on which rose an imposing structure of modified English-Georgian design with elegant details such as two imaginatively adorned chimneys, two large semicircular bay windows, and two fireplaces with mantels of hand-carved gray Italian marble.

Three days before Christmas the Crewses entertained their friends at an open house. Evergreen garlands embellished the huge winding staircase as well as the rest of the house. A splendid array of food covered the hand-carved walnut sideboards. A crystal bowl was kept filled with planter's punch; tea and coffee were available as well as decanters of the local wine, and the gentlemen were well supplied with Southern Comfort.

In the evening the sliding doors opened for dancing in both parlors. Seated in the second one, the older ladies chatted amiably and kept their chaperoning eyes on the dancing couples. In the library the gentlemen talked over business and politics as they sipped more Southern Comfort with Colonel Crews; here, too, they could smoke their cigars without offending the ladies. Such conspicuous consumption had been unknown in Franklin County when the Virginians had first arrived a half century before.

This beautiful house (now restored and open to the public as part of the Missouri Botanical Garden's Shaw Nature Reserve) was the setting for many a similar soiree in the decade that followed. Tom and Jinnie were known as an elegant, cultivated, and hospitable couple. One is reminded of the similar rich, full life led by John T. McCarty and his wife, Mary, in California two decades earlier.

Tom was fifty-two years old when he decided to enter the Congressional primaries for his district in 1884. A popular man, an experienced attorney, and an eloquent orator, he had the support of the Franklin County delegation, but the whole district was in a deadlock. His opponents claimed that if he and his Democrats were elected, they would recognize and reward the Rebels! The session was very dramatic; before it was over, delegates were kicking each other and screaming incoherently. One man wanted to change his vote so that Crews would receive the majority, but was denied that privilege, one of his neighboring delegates actually holding him back by sitting on him till the matter was settled. Crews lost by that single vote.

On June 25, 1891, Tom died of a kidney infection at Sisters Hospital in St. Louis. Jinnie lived another five and a half years. Both are buried in the cemetery at Pacific, a nearby town. Tom had outlived all the Immortal Six. (Sam Wilson had died in early 1889, the last survivor of the Founders.) How long he corresponded with his fellow Deltas is not a matter of record.

We can be certain, however, that his image remained in their minds all their lives. His spirit lives today in his many descendants who joined Phi Gamma Delta: one grandson, Sterling Crews Reynolds (Missouri 1913); and four great-grandsons, Elzie H. Musgrave (Missouri 1933), William A. Joplin, Jr. (Missouri 1940), Clarke Thomas Reed (Missouri 1950), and Robert C. Joplin (Missouri 1952).

We are proud to have in our earliest membership a man of the caliber of Thomas W. B. Crews - generous, brave, loyal, industrious, reliable, polished, lovable, a "god of boys," "noble and magnanimous" - in short a truly ideal Brother.